Analysis of Common Failure Modes in Electrical Connectors

2026-01-23 15:181. Introduction

The proliferation of electronic systems has driven exponential growth in the variety and complexity of electrical connectors. In this context, connector reliability transcends a simple component specification; it becomes a fundamental determinant of overall system uptime, safety, and lifecycle cost. A single connector failure can cascade into system malfunction, data loss, or operational downtime, with severe consequences in critical applications. As performance demands increase and operating environments become more challenging, the margin for error diminishes. Therefore, a proactive understanding of potential failure modes is not merely academic—it is an essential engineering practice. This analysis aims to move beyond symptomatic description, offering a root-cause-oriented examination of common failures and actionable, prevention-focused recommendations for designers, manufacturers, and quality assurance professionals.

2. Analysis of Common Connector Failure Modes

2.1 Abnormal Electrical Contact (Intermittency & High Resistance)

This is the most prevalent failure mode, manifesting as intermittent connections (chattering), open circuits, or a pathological increase in contact resistance leading to overheating. The root causes differ significantly based on the contact interface design philosophy.

2.1.1 Rigid Pin / Compliant Socket (Female) Connectors:

Primary Failure Mechanisms: Loss of contact normal force (insufficient separation force); insulating surface contamination; fretting corrosion.

In-Depth Analysis: Compliant sockets (e.g., cantilever beam, torsion spring, or crimp-style designs) rely on elastic deflection to generate a sustained normal force against the rigid pin. This force ensures metallic asperity contact through any surface films. Failures occur when:

Permanent Set/Deformation: Over-mating, misalignment (angled mating), or using an oversized pin can cause plastic deformation of the socket spring elements, leading to a permanent loss of contact force ("relaxation").

Surface Insulation: Deposits of dust, insulating oxides, organics (from outgassing), or silicone contamination create a barrier. Even thin films can significantly increase resistance, especially in low-voltage, high-reliability circuits.

Fretting Corrosion: Micro-motion between pin and socket due to vibration or thermal cycling wears through the precious metal plating (e.g., gold), exposing the base metal (e.g., nickel, copper) to oxidation, which builds up as an insulating layer.

2.1.2 Flexible (Spring) Pin / Rigid Socket Connectors:

Primary Failure Mechanisms: Insufficient or missing pin crown (the formed contact point); crimp termination failures; socket contamination or dimensional out-of-spec; pin depression ("pistoning").

In-Depth Analysis: Flexible pins, often wire-wound or stamped spring designs, feature a crowned contact area that compresses against the rigid socket wall.

Crown Defects: A missing, undersized, or misshapen crown results in a line or point contact with insufficient area and normal force. Causes include manufacturing errors (improper forming), crown damage during handling, or stress relaxation after repeated mating cycles without proper heat treatment (aging).

Crimp Failures: The crimp that attaches the pin to the wire is a critical subsystem. An undersized crimp barrel, worn tooling, or incorrect wire strand placement can cause high resistance and mechanical weakness at the crimp interface itself, which can masquerade as a pin-socket problem.

Socket Issues: An oversized socket inner diameter (ID) prevents adequate compression of the pin crown. Contamination inside the socket acts as an insulator.

Pin Depression/Pistoning: Excessive mating force, misalignment, or foreign object debris (FOD) in the socket can cause the entire pin contact to be pushed back into its insulator housing, preventing any engagement.

2.2 Dielectric / Electrical Performance Failure

This category involves the insulating body of the connector and includes failures of Insulation Resistance (IR) and Dielectric Withstanding Voltage (DWV).

Primary Failure Mechanisms: Surface or bulk contamination; moisture ingress; intrinsic insulation material defects; partial discharge; tracking.

In-Depth Analysis:

Conductive Path Formation: Hygroscopic contaminants (flux residues, salts, dust) absorb atmospheric moisture, forming a conductive electrolyte path across or through the insulator, leading to high leakage current and low IR.

Material & Process Defects: Voids, porosity, or cracks in the molded insulator (from poor processing) create localized high-field regions, initiating partial discharge (corona) that erodes the material, eventually leading to a full dielectric breakdown (arc). Metallic inclusions from contaminated resin act as field concentrators.

Tracking: Under high humidity and voltage, carbonized paths can form on the insulator surface due to electrical arcing across contaminants, creating a permanent low-resistance leakage path.

2.3 Mechanical & Interfacial Failure

These failures impair the connector's physical mating, unmating, and long-term integrity.

Interfacing/Mating Issues: Includes difficulty in engagement/disengagement and non-seating. Causes are often dimensional: housing warpage, bent pins, damaged lead-ins, burrs, or tolerances stacking incorrectly. Poor connector keying design exacerbates these issues.

Plating & Corrosion Failures: The contact plating (e.g., gold over nickel) is a sacrificial barrier.

Porosity: Thin or porous plating allows the underlying nickel diffusion barrier to be compromised, leading to base metal corrosion.

Poor Adhesion: Plating blistering or flaking exposes unprotected metal.

Galvanic Corrosion: In harsh environments, dissimilar metals in contact can create galvanic cells, accelerating corrosion.

Contact Retention Failure: The mechanism securing the contact within the insulator housing fails. This can be due to a damaged or missing housing latch, an under-sized contact retention barb, or housing damage from improper tool use. The result is "pistoning," where the contact pushes out during mating.

2.4 Hermeticity / Sealing Failure

For connectors specified as sealed (e.g., IP-rated, hermetic), leakage of gases or liquids is a critical failure.

Primary Failure Mechanisms: Incomplete material fusion; adhesive failures; inclusion-induced microcracks.

In-Depth Analysis:

Glass-to-Metal Seals: Failure arises from thermal expansion coefficient (CTE) mismatch between glass, metal shell, and pin, causing stress cracks during temperature cycling. Improper sealing furnace profiles are a common root cause.

Elastomeric/Potted Seals: Failures include adhesive de-bonding (from surface contamination or poor cure), incomplete filler wetting leaving voids, and compression set of O-rings over time, reducing sealing force.

3. Advanced Prevention Strategies & Best Practices

Mitigating connector failures requires a systems engineering approach spanning design, manufacturing, and application.

Design Phase:

Contact System: Select contact designs with proven reliability for the application's vibration, current, and mating cycle requirements. Use finite element analysis (FEA) to validate spring stresses.

Materials: Specify insulators with high Comparative Tracking Index (CTI), low moisture absorption, and suitable thermal properties. Define plating systems per ASTM B488 or MIL-DTL-45204, with appropriate thickness for the environment.

Sealing: Design for robust sealing, considering gland design for elastomers and CTE matching for glass seals.

Manufacturing & Process Control:

Cleanliness: Implement stringent cleanroom protocols (e.g., per IEST-STD-CC1246) for high-reliability assemblies. Use ionized air and conductive mats to control electrostatic discharge (ESD) and particulate attraction.

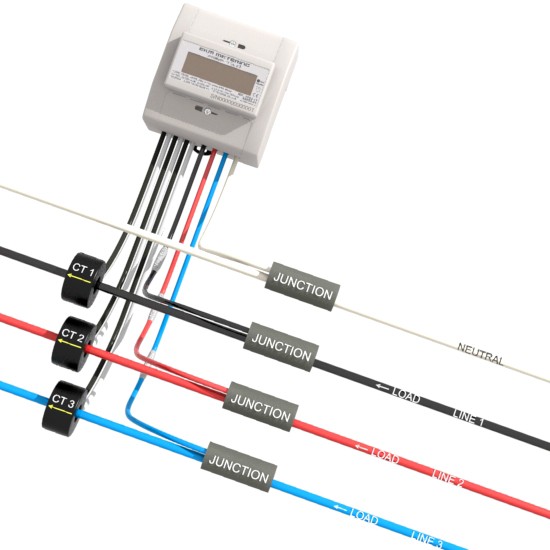

Crimping: Utilize calibrated, automatic crimping systems with periodic pull-force and microsection verification per IPC/WHMA-A-620. Maintain comprehensive crimp press monitoring data.

Inspection: Deploy automated optical inspection (AOI) for contact placement and defects. Use 100% electrical testing (Continuity, IR, DWV) as a final gate.

Application & Handling:

Training: Ensure operators are trained in proper mating/unmating techniques to avoid damage.

Protection: Use protective caps and covers when connectors are unmated. Implement connector savers in high-cycle test environments.

Condition Monitoring: For critical applications, consider periodic monitoring of contact resistance or use connectors with built-in health monitoring features.

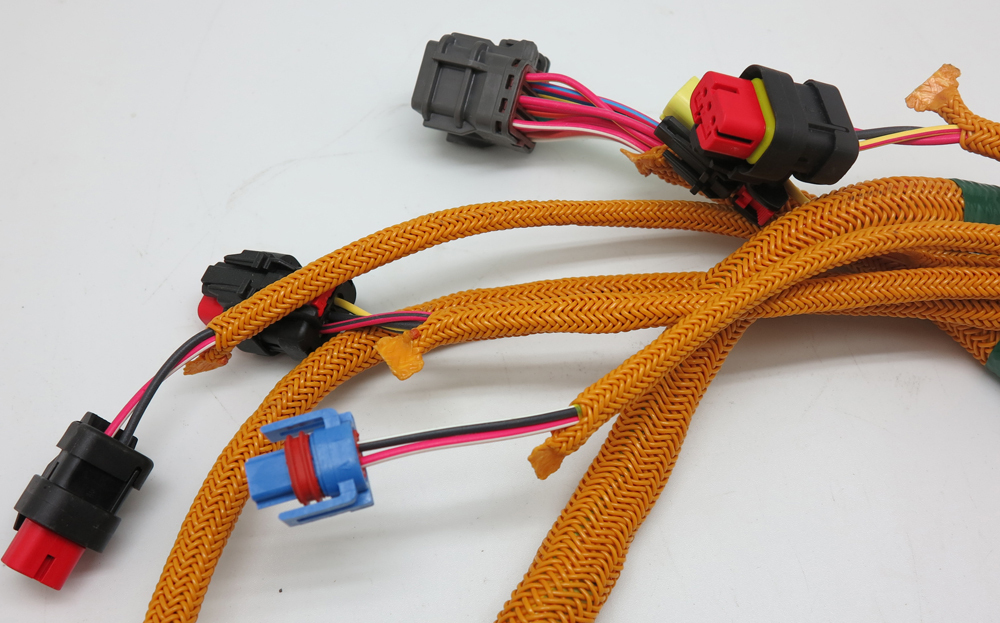

Conclusion: Connector reliability is a predictable science, not a matter of chance. By understanding the failure physics outlined above and implementing the corresponding control strategies, manufacturers can dramatically improve product lifespan and system performance. At Xiamen Kehan Electronics, our expertise in precision wire harness assembly and connector integration is built upon this deep failure mode analysis. We engineer resilience into every custom cable assembly, employing rigorous validation against wire harness crimping standards and application-specific environmental tests to deliver solutions where failure is not an option.